30회 중국의 항복선언?

2018년 3월 23일 방송

이춘근

Lee Choon Kun

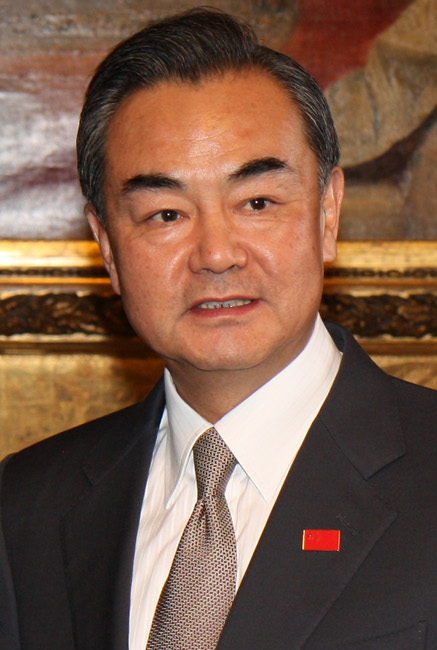

왕이 王毅 (1953~)

중화인민공화국 제11대 외교부장

베이징에서 태어난 왕이는 1969년 9월 고등학교를 졸업한 후 둥베이로 보내졌고,

헤이룽장 성에서 8년 동안 둥베이 건설 육군 군단에 복무하였다.

1977년 12월 베이징으로 돌아와 같은 해 베이징 제2외국어학원에서

일본어를 공부하여 1982년 2월 학사 학위를 취득하면서 졸업하였다.

1989년 9월~ 일본 주재 중화인민공화국 대사 5년 동안 근무

2018. 3. 8 베이징, 양회 兩會

(전국인민대표대회 · 전국인민정치협상회의)

"중국은

자기 자신을 현대화해 나가는 길도

아직 멀다"

"때문에 우리는 미국의 역할을 대신할 수도

대신할 필요도 없다"

"세계 최대 선진국인 미국과

최대 개발도상국인 중국의 협력은

두 나라는 물론

세계에 이익을 줄 것"

"중미(中美)는 경쟁을 할 수는 있지만,

적수가 될 필요는 없다"면서

"오히려 동료가 돼야 한다"고 강조했다

"일부 미국 인사가

중국이 미국의 국제적 역할을

차지하려 한다고 주장하는데

이는 근본적으로 잘못된 전략적 오판"

"우리가 걷는 길은

중국 특색의 사회주의의 길이며,

핵심은 평화적으로 발전하는 것이며,

그 성공은 함께 승리하는 데 있다"

2018. 3. 8 양회(兩會)

(전국인민대표대회 · 전국인민정치협상회의)

왕이 王毅 (1953~)

중화인민공화국 제11대 외교부장

개발도상국 (開發途上國, developing country)

약칭 개도국은 선진국에 비해 산업의 근대화와 경제 개발이 크게 뒤지고 있어

현재 경제 성장을 목표로 하는 나라를 일컫는다

보통 후진국과 같은 뜻으로 통용되며, 발전도상국이라고도 한다

외국산 철강과 알루미늄에

'보복관세'를 부과한다고 발표!

이에 따라 철강에는 25%,

알루미늄에는 10% 관세가 부과

2018. 3. 8 (현지시간)

도널드 트럼프 미국 대통령이 지난 8일 백악관에서 미국 철강업계 노동자들이 지켜보는 가운데,

수입 철강과 알루미늄에 새로운 관세를 부과하는 행정명령에 서명했다.

일본도 중국에 '시장경제지위' 부여 않기로

입력 2016.12.05 20:05 수정 2016.12.06 03:13 지면 A11

미국 · EU 이어 통상압박 강화

중국산 제품 특혜관세도 폐지

중국, WTO에 제소 가능성

일본 정부가 중국을 세계무역기구(WTO) 협정상 ‘시장경제국’으로 인정하지 않기로 방침을 정했다. 지난달 23일 중국산 제품에 적용해온 특혜관세(우대관세)를 폐지하기로 한 데 이어 시장경제지위도 부여하지 않기로 하면서 중·일 간 통상 마찰이 심화될 것이란 전망이 나온다.

5일 요미우리신문에 따르면 일본 정부는 미국, 유럽연합(EU)과 보조를 맞춰 중국을 시장경제국으로 인정하지 않고 경제자유화와 개혁을 요구하기로 했다.

WTO 협정은 보조금 등을 통해 자국 산업을 보호하고 수출을 부당하게 지원하는 국가를 ‘비시장경제국가’로 지정해 수출품에 대한 반덤핑관세 등 대응 조치를 하기 쉽도록 규정하고 있다. 2001년 WTO에 가입한 중국은 그동안 비시장경제국으로 있었지만 15년이 되는 오는 11일 자동으로 시장경제지위를 획득해야 한다고 주장했다. 일본 정부는 중국산 폴리우레탄 재료 등 3개 품목에 반덤핑 관세를 부과하고 있다.

요미우리신문은 일본 정부가 미국, EU와 함께 중국에 시장경제지위를 부여하지 않기로 결정해 대(對)중 무역공세에 나선 것이라고 분석했다. 일본에 앞서 지난달 페니 프리츠커 미국 상무장관은 “중국은 시장경제지위로 옮겨갈 여건에 이르지 못했다”며 같은 의견을 밝혔다. 유럽의회도 지난달 중국의 시장경제지위 부여에 반대하는 결의안을 채택했다.

미국, EU, 일본과 달리 한국과 호주는 이미 중국을 시장경제국으로 인정했다. 중국은 다른 나라에 대해서도 시장경제지위를 부여해줄 것을 요구하고 있다. 요미우리는 “중국이 미국과 EU, 일본의 시장경제지위 거부에 반발해 WTO에 제소하는 등의 방법을 동원할 가능성이 있다”고 전했다. 지난달 23일 미국 워싱턴DC에서 열린 미·중 상무위원회에 참석한 중국 상무부 국제무역부의 장샹천 부대표는 기자회견에서 “중국도 WTO 회원국이 누리는 권리를 보장받을 권리가 있다”고 강조했다.

■ 시장경제지위

원가, 임금, 환율, 가격 등을 시장이 결정하는 경제체제를 갖춘 국가로 상대교역국이 인정하는 것을 말한다.

시장경제지위를 인정받지 못하면 반덤핑 제소를 당했을 때 제3국의 가격 기준으로 덤핑 여부가 판정되는 불이익을 당한다. 중국은 2001년 세계무역기구(WTO)에 가입할 당시 최장 15년간 ‘비시장경제지위’를 감수하기로 했다.

도쿄=서정환 특파원 ceoseo@hankyung.com

미국 · EU 이어 일본도 대 중국 통상압박 강화

한국경제신문 2017. 12. 6

중국

한류 금한령

홈쇼핑 제한

무역 규제강화

한국 단체관광 금지 등

사드 보복

WTO 제소 철회

미국

철강, 알루미늄 수입제한 권고

철강 관세 등

보호 무역 조치

WTO 제소 시사

불합리한 보호 무역 조치에 대해서는

세계무역기구(WTO) 제소 등

당당하고 결연히 대응해 나가야 한다

2018. 2. 19 문재인 대통령

[천영우 칼럼]중국은 본래 그런 나라다

천영우 객원논설위원 한반도미래포럼 이사장 입력 2017-03-09 03:00수정 2017-03-09 09:20

大國답지 않은 사드 보복이 패권적 중화질서의 본색이다

사드 번복 시사한 野대선주자, 사드 불가피성 못 밝힌 정부, 저자세 외교로는 능멸 자초할 뿐

미국에 대한 보복으로 간주하고 한미동맹 차원의 대처 조율하라

천영우 객원논설위원 한반도미래포럼 이사장

정부의 사드 배치 결정에 대한 중국의 보복이 갈수록 난폭해지고 있다. 보복 범위를 ‘한한령(限韓令)’에서 롯데그룹의 중국 내 영업과 중국인의 한국 관광으로 확대하면서도 증거를 남기지 않으려고 법 집행과 업계의 자발적 조치로 교묘하게 위장하고 있다. 중국에 대한 무역보복의 빌미를 찾으려 부심하는 미국 도널드 트럼프 행정부에 명분을 주지 않으려는 비겁한 잔꾀다. 아직 우리 상품의 수입 규제에 나서지 못하는 이유는 무역에서는 우리가 갑의 입장에 있기 때문이다. 대중(對中) 수출상품의 95%는 중국의 수출산업을 지탱하는 데 필수불가결한 소재와 부품이다.

그런데도 중국이 대국으로서의 금도와 이성을 상실하고 치졸함과 오만의 한계를 계속 경신해 가는 이유는 무엇일까? 답은 간단하다. 중국은 본래 그런 나라다. 그간 동아시아의 전략적 게임에서 우리를 중국 편에 끌어들이려고 공들여 구애하던 친절한 가면 뒤의 민낯과 본심이 만천하에 드러난 것뿐이다. 패권적 중화질서의 본질은 주변국에 대해 자국 이익에 부합하는 범위 내에서 제한적 주권만 허용하겠다는 것이다.

그러나 중국만 탓할 일은 아니다. 중국에 사드 배치 결정이 번복될 수도 있다는 환상을 심어준 것이 화를 키웠고, 이를 조장한 것은 국내 정치와 국론 분열이다. 민주당의 유력 대선 후보가 사드 배치를 차기 정부로 넘기라고 하는 데서 중국은 번복의 희망을 볼 것이다. 집권 후 번복할 생각이 없다면 집권하자마자 중국과 대립할 ‘뜨거운 감자’를 떠안겠다고 자청할 리가 없고, 한중 관계의 악재를 현 정부 임기 내에 털어주기를 바랄 것이기 때문이다. 정치인들이 중국에 몰려가 보복을 자제해 달라고 비굴하게 부탁한 것도 보복의 신통한 효과를 확인시켜 줌으로써 더 강도 높은 보복을 청탁한 셈이 되었다.

정부의 어설픈 대처도 문제를 키웠다. 사드가 불가피한 이유는 한중관계가 밀월을 누릴 때 설명했어야 한다. 북한이 일정 시한 내에 비핵화 결단을 내리고 구체적 행동으로 나오지 않는 한 우리는 부득이 사드 배치를 포함해 북한의 핵·미사일 공격을 막아내는 데 필요한 모든 자구적 조치를 강구할 수밖에 없다는 사실을 정상회담 때마다 중국 측에 분명히 해두었다면 이토록 막무가내로 나오기는 어려웠을 것이다.

정부가 중국을 계속 설득해 보겠다는 것도 안이하고 군색하기 짝이 없는 자세다. 우리와 안보 이해관계가 대립되는 나라에 5000만 국민의 생사와 안위가 걸린 문제를 놓고 발언권을 허용하는 것은 무책임하고 위험한 일이다. 협의와 설득이 아니라 사전에 통보하고 관심이 있으면 친절하게 설명해줄 수 있는 사안일 뿐이다.

우리가 약소국이란 이유만으로 중국이 얕잡아 보고 함부로 대하는 것은 아니다. 베트남처럼 경제적 사활을 중국에 의존하면서도 국가의 주권과 영토를 지키기 위해서라면 전쟁도 불사하겠다는 결기로 온 국민이 하나 된 나라라면 감히 시비할 엄두를 못 낼 것이다. 야당과 정부의 저자세는 중국의 능멸과 더 큰 보복을 자초할 뿐이다.

중국의 몽니에 대한 해법도 국내 대선 결과에 따라 사드 배치 결정을 뒤집을 수 있다는 미련을 버리게 하는 데서 찾아야 한다. 첫째, 대통령 선거 이전에 사드 배치를 완료하고 임시 가동해야 한다. 차기 정부에 이 무거운 짐을 떠넘기지 말고 새 정부는 사드 배치를 기정사실화한 바탕 위에서 한중관계를 리셋하도록 해야 한다. 야당도 모호하고 무책임한 입장을 버려야 한다.

둘째, 한미동맹 차원의 자위적 조치에 대한 보복 조치는 미국에 대한 보복 조치로 간주하여 대응하도록 한미 간에 긴밀히 조율해야 한다.

끝으로, 중국에 대한 경제 의존도와 중국 리스크에 대한 과도한 노출을 중장기적으로 줄여 나가고 우리와 안보 우려 및 전략적 이해관계를 공유하는 베트남 인도 등으로 투자와 무역을 다변화해 가야 한다. 안보 이해관계가 일치하는 국가와는 경제적 의존도가 심화될수록 안보와 경제 간 상호 보강효과를 발휘하지만 그렇지 못하면 경제적 의존도가 안보적 취약점이 될 수 있다.

안보를 둘러싼 충돌은 사드가 시작에 불과하다. 중국은 안보적 이익을 위해 언제든 경제적 압박수단을 동원할 국가라는 전제 아래 민간기업들도 중국 리스크를 재평가하고 적극적인 헤징 전략을 세워야 한다. 중국은 더 이상 우리의 엘도라도가 아니다.

천영우 객원논설위원 한반도미래포럼 이사장

무역에서는 우리나라가 갑의 입장!

대중(對中) 수출 상품의 95%는

중국의 수출산업을 지탱하는 데 필수불가결한 소재와 부품이다

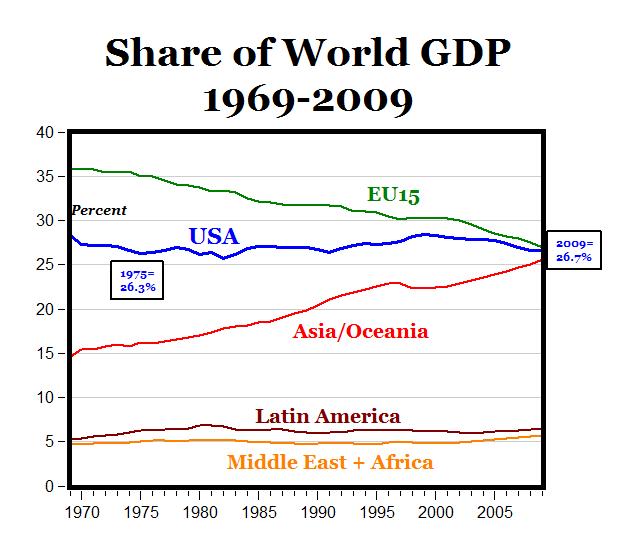

경제도 미국이 중국보다 더욱 중요하다

2017년 중국은 미국으로부터 3,700억 달러 무역 흑자

중국이 곧 1등이 되리라는 과거 예측들

2011년 국제통화기금 (IMF)는 놀라운 경제전망 예측치를 내놓았다.

중국이 미국을 앞질러 세계 최대의 경제가 될 것이라는 전망인데

중국은 2016년 미국을 앞서 세계 최대의 경제 대국이 되리라는 것이었다.

세계은행 2014년 중국이 미국을 앞선다고 보도 (2014. 5. 1. 한국 신문들에도...)

옥스포드 대학 출신 경제학자.

Peterson Instityte for International Economics의 수석 경제학자 Arbind Subramanian, Eclipse

: Living in the Shadow of China's Economic Dominance에서 2016년은 예상보다 빨리 다가올지도 모른다.

이미 미국을 앞섰는지도 모른다고 주장했다.

Jim O'Neil 골드만 삭스 - 브릭스라는 용어 고안한 사람 - 중국은 2017년 Number One.

American Intelligence Community의 Think Tank인 National Intelligence Council은 2030년에 중국이 미국을 앞선다.

[Number One by 2027 : Jim O'Neil, Growth Map : Economic Opportunity in the BRICs and Beyond

(New York : Portfolio / Penguin, 2011)]

[Number one in 2030 : National Intelligence Council.

"Global Trends 2030 : Alternative Worlds," December 2012, Krutzman 각주 269 4. 269쪽

정글만리

- 조정래

약육강식이 지배하는 중국의 비지니스 현장을 묘사, 2013년 발표한 장편소설

| GDP / USD | Population 10,000 |

GDP / capita (1인당) |

|

| America 미국 |

18,624,450 (1) |

32,446 (03) |

59,745 (7) |

| China 중국 |

11,232,108 (2) |

140,952 (01) |

8,582 (73) |

| Japan 일본 |

4,936,543 (3) |

12,748 (11) |

38,550 (23) |

| Russia 러시아 |

1,283,162 (12) |

14,399 (09) |

10,248 (65) |

| Korea 한국 |

1,411,042 (11) |

5,098 (27) |

29,730 (26) |

World Average (세계 평균) 10,038$

기 소르망 Guy Sorman (1944~)

기 소르망 Guy Sorman (1944~)

Q. 지난 2007년 - 2008년 믹구 금융위기 후 미국 모델 대신 중국 모델이 새롭게 평가되고 있다는 지적을 하는데...?

"세상의 어떤 나라도

중국을 모델로 삼고 있지는 않다"

Q. 그런 미국의 파워가 요즘 들어 쇠퇴하고 있다는 지적이 많은데...?

"그런 주장에 전혀 동의할 수 없다"

Q. 중국이 부상하고 있지 않는가?

"중국은 빈곤한 국가다"

Decline of the United States of America

Superdollar 또는 Superbill 또는 Supernote 또는 Superk라고도 한다

매우 높은 품질의 위조된 미국 100달러 지폐

트럼프 시대의 달러

: 미국과 달러의 미래를 전망하다

- 오세준 (2017. 1)

미국이 초강대국이라서 달러가 기축통화가 되었지만,

미국이 공들여 만든 최고의 상품인 달러의 힘으로

초강대국의 지위를 유지하는데 도움이 되고 있다. (p. 103)

'Exorbitant privilege' 과도한 특권!

앞으로 3년, 미국 랠리에 올라 타라

- 양연정 (2017. 3)

"America's Pacific Century"

미국의 태평양 세기

The future of politics will be decided in Asia,

not Afganistan or Iraq,

and the United States will be right

at the center of the action.

세계정치의 미래는 아시아에서 결정될 것이다.

아프간이나 이라크에서가 아니다.

미국은 아시아 한복판에 가 있을 것이다.

2011. October, Foreigh Policy

Hillary Clinton 국무장관 기고문

FEATURE

America’s Pacific Century

The future of politics will be decided in Asia, not Afghanistan or Iraq, and the United States will be right at the center of the action.

Introducing FP's new economics podcast, Ones and Tooze

Join FP columnist Adam Tooze and deputy editor Cameron Abadi as they explain the week's biggest economic news, from debt ceiling negotiations to why the fortunes of China's property market matter to the world.

As the war in Iraq winds down and America begins to withdraw its forces from Afghanistan, the United States stands at a pivot point. Over the last 10 years, we have allocated immense resources to those two theaters. In the next 10 years, we need to be smart and systematic about where we invest time and energy, so that we put ourselves in the best position to sustain our leadership, secure our interests, and advance our values. One of the most important tasks of American statecraft over the next decade will therefore be to lock in a substantially increased investment — diplomatic, economic, strategic, and otherwise — in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Asia-Pacific has become a key driver of global politics. Stretching from the Indian subcontinent to the western shores of the Americas, the region spans two oceans — the Pacific and the Indian — that are increasingly linked by shipping and strategy. It boasts almost half the world’s population. It includes many of the key engines of the global economy, as well as the largest emitters of greenhouse gases. It is home to several of our key allies and important emerging powers like China, India, and Indonesia.

At a time when the region is building a more mature security and economic architecture to promote stability and prosperity, U.S. commitment there is essential. It will help build that architecture and pay dividends for continued American leadership well into this century, just as our post-World War II commitment to building a comprehensive and lasting transatlantic network of institutions and relationships has paid off many times over — and continues to do so. The time has come for the United States to make similar investments as a Pacific power, a strategic course set by President Barack Obama from the outset of his administration and one that is already yielding benefits.

With Iraq and Afghanistan still in transition and serious economic challenges in our own country, there are those on the American political scene who are calling for us not to reposition, but to come home. They seek a downsizing of our foreign engagement in favor of our pressing domestic priorities. These impulses are understandable, but they are misguided. Those who say that we can no longer afford to engage with the world have it exactly backward — we cannot afford not to. From opening new markets for American businesses to curbing nuclear proliferation to keeping the sea lanes free for commerce and navigation, our work abroad holds the key to our prosperity and security at home. For more than six decades, the United States has resisted the gravitational pull of these "come home" debates and the implicit zero-sum logic of these arguments. We must do so again.

Beyond our borders, people are also wondering about America’s intentions — our willingness to remain engaged and to lead. In Asia, they ask whether we are really there to stay, whether we are likely to be distracted again by events elsewhere, whether we can make — and keep — credible economic and strategic commitments, and whether we can back those commitments with action. The answer is: We can, and we will.

Harnessing Asia’s growth and dynamism is central to American economic and strategic interests and a key priority for President Obama. Open markets in Asia provide the United States with unprecedented opportunities for investment, trade, and access to cutting-edge technology. Our economic recovery at home will depend on exports and the ability of American firms to tap into the vast and growing consumer base of Asia. Strategically, maintaining peace and security across the Asia-Pacific is increasingly crucial to global progress, whether through defending freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, countering the proliferation efforts of North Korea, or ensuring transparency in the military activities of the region’s key players.

Just as Asia is critical to America’s future, an engaged America is vital to Asia’s future. The region is eager for our leadership and our business — perhaps more so than at any time in modern history. We are the only power with a network of strong alliances in the region, no territorial ambitions, and a long record of providing for the common good. Along with our allies, we have underwritten regional security for decades — patrolling Asia’s sea lanes and preserving stability — and that in turn has helped create the conditions for growth. We have helped integrate billions of people across the region into the global economy by spurring economic productivity, social empowerment, and greater people-to-people links. We are a major trade and investment partner, a source of innovation that benefits workers and businesses on both sides of the Pacific, a host to 350,000 Asian students every year, a champion of open markets, and an advocate for universal human rights.

President Obama has led a multifaceted and persistent effort to embrace fully our irreplaceable role in the Pacific, spanning the entire U.S. government. It has often been a quiet effort. A lot of our work has not been on the front pages, both because of its nature — long-term investment is less exciting than immediate crises — and because of competing headlines in other parts of the world.

As secretary of state, I broke with tradition and embarked on my first official overseas trip to Asia. In my seven trips since, I have had the privilege to see firsthand the rapid transformations taking place in the region, underscoring how much the future of the United States is intimately intertwined with the future of the Asia-Pacific. A strategic turn to the region fits logically into our overall global effort to secure and sustain America’s global leadership. The success of this turn requires maintaining and advancing a bipartisan consensus on the importance of the Asia-Pacific to our national interests; we seek to build upon a strong tradition of engagement by presidents and secretaries of state of both parties across many decades. It also requires smart execution of a coherent regional strategy that accounts for the global implications of our choices.

WHAT DOES THAT regional strategy look like? For starters, it calls for a sustained commitment to what I have called "forward-deployed" diplomacy. That means continuing to dispatch the full range of our diplomatic assets — including our highest-ranking officials, our development experts, our interagency teams, and our permanent assets — to every country and corner of the Asia-Pacific region. Our strategy will have to keep accounting for and adapting to the rapid and dramatic shifts playing out across Asia. With this in mind, our work will proceed along six key lines of action: strengthening bilateral security alliances; deepening our working relationships with emerging powers, including with China; engaging with regional multilateral institutions; expanding trade and investment; forging a broad-based military presence; and advancing democracy and human rights.

By virtue of our unique geography, the United States is both an Atlantic and a Pacific power. We are proud of our European partnerships and all that they deliver. Our challenge now is to build a web of partnerships and institutions across the Pacific that is as durable and as consistent with American interests and values as the web we have built across the Atlantic. That is the touchstone of our efforts in all these areas.

Our treaty alliances with Japan, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, and Thailand are the fulcrum for our strategic turn to the Asia-Pacific. They have underwritten regional peace and security for more than half a century, shaping the environment for the region’s remarkable economic ascent. They leverage our regional presence and enhance our regional leadership at a time of evolving security challenges.

As successful as these alliances have been, we can’t afford simply to sustain them — we need to update them for a changing world. In this effort, the Obama administration is guided by three core principles. First, we have to maintain political consensus on the core objectives of our alliances. Second, we have to ensure that our alliances are nimble and adaptive so that they can successfully address new challenges and seize new opportunities. Third, we have to guarantee that the defense capabilities and communications infrastructure of our alliances are operationally and materially capable of deterring provocation from the full spectrum of state and nonstate actors.

The alliance with Japan, the cornerstone of peace and stability in the region, demonstrates how the Obama administration is giving these principles life. We share a common vision of a stable regional order with clear rules of the road — from freedom of navigation to open markets and fair competition. We have agreed to a new arrangement, including a contribution from the Japanese government of more than $5 billion, to ensure the continued enduring presence of American forces in Japan, while expanding joint intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance activities to deter and react quickly to regional security challenges, as well as information sharing to address cyberthreats. We have concluded an Open Skies agreement that will enhance access for businesses and people-to-people ties, launched a strategic dialogue on the Asia-Pacific, and been working hand in hand as the two largest donor countries in Afghanistan.

Similarly, our alliance with South Korea has become stronger and more operationally integrated, and we continue to develop our combined capabilities to deter and respond to North Korean provocations. We have agreed on a plan to ensure successful transition of operational control during wartime and anticipate successful passage of the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement. And our alliance has gone global, through our work together in the G-20 and the Nuclear Security Summit and through our common efforts in Haiti and Afghanistan.

We are also expanding our alliance with Australia from a Pacific partnership to an Indo-Pacific one, and indeed a global partnership. From cybersecurity to Afghanistan to the Arab Awakening to strengthening regional architecture in the Asia-Pacific, Australia’s counsel and commitment have been indispensable. And in Southeast Asia, we are renewing and strengthening our alliances with the Philippines and Thailand, increasing, for example, the number of ship visits to the Philippines and working to ensure the successful training of Filipino counterterrorism forces through our Joint Special Operations Task Force in Mindanao. In Thailand — our oldest treaty partner in Asia — we are working to establish a hub of regional humanitarian and disaster relief efforts in the region.

AS WE UPDATE our alliances for new demands, we are also building new partnerships to help solve shared problems. Our outreach to China, India, Indonesia, Singapore, New Zealand, Malaysia, Mongolia, Vietnam, Brunei, and the Pacific Island countries is all part of a broader effort to ensure a more comprehensive approach to American strategy and engagement in the region. We are asking these emerging partners to join us in shaping and participating in a rules-based regional and global order.

One of the most prominent of these emerging partners is, of course, China. Like so many other countries before it, China has prospered as part of the open and rules-based system that the United States helped to build and works to sustain. And today, China represents one of the most challenging and consequential bilateral relationships the United States has ever had to manage. This calls for careful, steady, dynamic stewardship, an approach to China on our part that is grounded in reality, focused on results, and true to our principles and interests.

We all know that fears and misperceptions linger on both sides of the Pacific. Some in our country see China’s progress as a threat to the United States; some in China worry that America seeks to constrain China’s growth. We reject both those views. The fact is that a thriving America is good for China and a thriving China is good for America. We both have much more to gain from cooperation than from conflict. But you cannot build a relationship on aspirations alone. It is up to both of us to more consistently translate positive words into effective cooperation — and, crucially, to meet our respective global responsibilities and obligations. These are the things that will determine whether our relationship delivers on its potential in the years to come. We also have to be honest about our differences. We will address them firmly and decisively as we pursue the urgent work we have to do together. And we have to avoid unrealistic expectations.

Over the last two-and-a-half years, one of my top priorities has been to identify and expand areas of common interest, to work with China to build mutual trust, and to encourage China’s active efforts in global problem-solving. This is why Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and I launched the Strategic and Economic Dialogue, the most intensive and expansive talks ever between our governments, bringing together dozens of agencies from both sides to discuss our most pressing bilateral issues, from security to energy to human rights.

We are also working to increase transparency and reduce the risk of miscalculation or miscues between our militaries. The United States and the international community have watched China’s efforts to modernize and expand its military, and we have sought clarity as to its intentions. Both sides would benefit from sustained and substantive military-to-military engagement that increases transparency. So we look to Beijing to overcome its reluctance at times and join us in forging a durable military-to-military dialogue. And we need to work together to strengthen the Strategic Security Dialogue, which brings together military and civilian leaders to discuss sensitive issues like maritime security and cybersecurity.

As we build trust together, we are committed to working with China to address critical regional and global security issues. This is why I have met so frequently — often in informal settings — with my Chinese counterparts, State Councilor Dai Bingguo and Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi, for candid discussions about important challenges like North Korea, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and developments in the South China Sea.

On the economic front, the United States and China need to work together to ensure strong, sustained, and balanced future global growth. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the United States and China worked effectively through the G-20 to help pull the global economy back from the brink. We have to build on that cooperation. U.S. firms want fair opportunities to export to China’s growing markets, which can be important sources of jobs here in the United States, as well as assurances that the $50 billion of American capital invested in China will create a strong foundation for new market and investment opportunities that will support global competitiveness. At the same time, Chinese firms want to be able to buy more high-tech products from the United States, make more investments here, and be accorded the same terms of access that market economies enjoy. We can work together on these objectives, but China still needs to take important steps toward reform. In particular, we are working with China to end unfair discrimination against U.S. and other foreign companies or against their innovative technologies, remove preferences for domestic firms, and end measures that disadvantage or appropriate foreign intellectual property. And we look to China to take steps to allow its currency to appreciate more rapidly, both against the dollar and against the currencies of its other major trading partners. Such reforms, we believe, would not only benefit both our countries (indeed, they would support the goals of China’s own five-year plan, which calls for more domestic-led growth), but also contribute to global economic balance, predictability, and broader prosperity.

Of course, we have made very clear, publicly and privately, our serious concerns about human rights. And when we see reports of public-interest lawyers, writers, artists, and others who are detained or disappeared, the United States speaks up, both publicly and privately, with our concerns about human rights. We make the case to our Chinese colleagues that a deep respect for international law and a more open political system would provide China with a foundation for far greater stability and growth — and increase the confidence of China’s partners. Without them, China is placing unnecessary limitations on its own development.

At the end of the day, there is no handbook for the evolving U.S.-China relationship. But the stakes are much too high for us to fail. As we proceed, we will continue to embed our relationship with China in a broader regional framework of security alliances, economic networks, and social connections.

Among key emerging powers with which we will work closely are India and Indonesia, two of the most dynamic and significant democratic powers of Asia, and both countries with which the Obama administration has pursued broader, deeper, and more purposeful relationships. The stretch of sea from the Indian Ocean through the Strait of Malacca to the Pacific contains the world’s most vibrant trade and energy routes. Together, India and Indonesia already account for almost a quarter of the world’s population. They are key drivers of the global economy, important partners for the United States, and increasingly central contributors to peace and security in the region. And their importance is likely to grow in the years ahead.

President Obama told the Indian parliament last year that the relationship between India and America will be one of the defining partnerships of the 21st century, rooted in common values and interests. There are still obstacles to overcome and questions to answer on both sides, but the United States is making a strategic bet on India’s future — that India’s greater role on the world stage will enhance peace and security, that opening India’s markets to the world will pave the way to greater regional and global prosperity, that Indian advances in science and technology will improve lives and advance human knowledge everywhere, and that India’s vibrant, pluralistic democracy will produce measurable results and improvements for its citizens and inspire others to follow a similar path of openness and tolerance. So the Obama administration has expanded our bilateral partnership; actively supported India’s Look East efforts, including through a new trilateral dialogue with India and Japan; and outlined a new vision for a more economically integrated and politically stable South and Central Asia, with India as a linchpin.

We are also forging a new partnership with Indonesia, the world’s third-largest democracy, the world’s most populous Muslim nation, and a member of the G-20. We have resumed joint training of Indonesian special forces units and signed a number of agreements on health, educational exchanges, science and technology, and defense. And this year, at the invitation of the Indonesian government, President Obama will inaugurate American participation in the East Asia Summit. But there is still some distance to travel — we have to work together to overcome bureaucratic impediments, lingering historical suspicions, and some gaps in understanding each other’s perspectives and interests.

EVEN AS WE strengthen these bilateral relationships, we have emphasized the importance of multilateral cooperation, for we believe that addressing complex transnational challenges of the sort now faced by Asia requires a set of institutions capable of mustering collective action. And a more robust and coherent regional architecture in Asia would reinforce the system of rules and responsibilities, from protecting intellectual property to ensuring freedom of navigation, that form the basis of an effective international order. In multilateral settings, responsible behavior is rewarded with legitimacy and respect, and we can work together to hold accountable those who undermine peace, stability, and prosperity.

So the United States has moved to fully engage the region’s multilateral institutions, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, mindful that our work with regional institutions supplements and does not supplant our bilateral ties. There is a demand from the region that America play an active role in the agenda-setting of these institutions — and it is in our interests as well that they be effective and responsive.

That is why President Obama will participate in the East Asia Summit for the first time in November. To pave the way, the United States has opened a new U.S. Mission to ASEAN in Jakarta and signed the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation with ASEAN. Our focus on developing a more results-oriented agenda has been instrumental in efforts to address disputes in the South China Sea. In 2010, at the ASEAN Regional Forum in Hanoi, the United States helped shape a regionwide effort to protect unfettered access to and passage through the South China Sea, and to uphold the key international rules for defining territorial claims in the South China Sea’s waters. Given that half the world’s merchant tonnage flows through this body of water, this was a consequential undertaking. And over the past year, we have made strides in protecting our vital interests in stability and freedom of navigation and have paved the way for sustained multilateral diplomacy among the many parties with claims in the South China Sea, seeking to ensure disputes are settled peacefully and in accordance with established principles of international law.

We have also worked to strengthen APEC as a serious leaders-level institution focused on advancing economic integration and trade linkages across the Pacific. After last year’s bold call by the group for a free trade area of the Asia-Pacific, President Obama will host the 2011 APEC Leaders’ Meeting in Hawaii this November. We are committed to cementing APEC as the Asia-Pacific’s premier regional economic institution, setting the economic agenda in a way that brings together advanced and emerging economies to promote open trade and investment, as well as to build capacity and enhance regulatory regimes. APEC and its work help expand U.S. exports and create and support high-quality jobs in the United States, while fostering growth throughout the region. APEC also provides a key vehicle to drive a broad agenda to unlock the economic growth potential that women represent. In this regard, the United States is committed to working with our partners on ambitious steps to accelerate the arrival of the Participation Age, where every individual, regardless of gender or other characteristics, is a contributing and valued member of the global marketplace.

In addition to our commitment to these broader multilateral institutions, we have worked hard to create and launch a number of "minilateral" meetings, small groupings of interested states to tackle specific challenges, such as the Lower Mekong Initiative we launched to support education, health, and environmental programs in Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, and the Pacific Islands Forum, where we are working to support its members as they confront challenges from climate change to overfishing to freedom of navigation. We are also starting to pursue new trilateral opportunities with countries as diverse as Mongolia, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, and South Korea. And we are setting our sights as well on enhancing coordination and engagement among the three giants of the Asia-Pacific: China, India, and the United States.

In all these different ways, we are seeking to shape and participate in a responsive, flexible, and effective regional architecture — and ensure it connects to a broader global architecture that not only protects international stability and commerce but also advances our values.

OUR EMPHASIS ON the economic work of APEC is in keeping with our broader commitment to elevate economic statecraft as a pillar of American foreign policy. Increasingly, economic progress depends on strong diplomatic ties, and diplomatic progress depends on strong economic ties. And naturally, a focus on promoting American prosperity means a greater focus on trade and economic openness in the Asia-Pacific. The region already generates more than half of global output and nearly half of global trade. As we strive to meet President Obama’s goal of doubling exports by 2015, we are looking for opportunities to do even more business in Asia. Last year, American exports to the Pacific Rim totaled $320 billion, supporting 850,000 American jobs. So there is much that favors us as we think through this repositioning.

When I talk to my Asian counterparts, one theme consistently stands out: They still want America to be an engaged and creative partner in the region’s flourishing trade and financial interactions. And as I talk with business leaders across our own nation, I hear how important it is for the United States to expand our exports and our investment opportunities in Asia’s dynamic markets.

Last March in APEC meetings in Washington, and again in Hong Kong in July, I laid out four attributes that I believe characterize healthy economic competition: open, free, transparent, and fair. Through our engagement in the Asia-Pacific, we are helping to give shape to these principles and showing the world their value.

We are pursuing new cutting-edge trade deals that raise the standards for fair competition even as they open new markets. For instance, the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement will eliminate tariffs on 95 percent of U.S. consumer and industrial exports within five years and support an estimated 70,000 American jobs. Its tariff reductions alone could increase exports of American goods by more than $10 billion and help South Korea’s economy grow by 6 percent. It will level the playing field for U.S. auto companies and workers. So, whether you are an American manufacturer of machinery or a South Korean chemicals exporter, this deal lowers the barriers that keep you from reaching new customers.

We are also making progress on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which will bring together economies from across the Pacific — developed and developing alike — into a single trading community. Our goal is to create not just more growth, but better growth. We believe trade agreements need to include strong protections for workers, the environment, intellectual property, and innovation. They should also promote the free flow of information technology and the spread of green technology, as well as the coherence of our regulatory system and the efficiency of supply chains. Ultimately, our progress will be measured by the quality of people’s lives — whether men and women can work in dignity, earn a decent wage, raise healthy families, educate their children, and take hold of the opportunities to improve their own and the next generation’s fortunes. Our hope is that a TPP agreement with high standards can serve as a benchmark for future agreements — and grow to serve as a platform for broader regional interaction and eventually a free trade area of the Asia-Pacific.

Achieving balance in our trade relationships requires a two-way commitment. That’s the nature of balance — it can’t be unilaterally imposed. So we are working through APEC, the G-20, and our bilateral relationships to advocate for more open markets, fewer restrictions on exports, more transparency, and an overall commitment to fairness. American businesses and workers need to have confidence that they are operating on a level playing field, with predictable rules on everything from intellectual property to indigenous innovation.

ASIA’S REMARKABLE ECONOMIC growth over the past decade and its potential for continued growth in the future depend on the security and stability that has long been guaranteed by the U.S. military, including more than 50,000 American servicemen and servicewomen serving in Japan and South Korea. The challenges of today’s rapidly changing region — from territorial and maritime disputes to new threats to freedom of navigation to the heightened impact of natural disasters — require that the United States pursue a more geographically distributed, operationally resilient, and politically sustainable force posture.

We are modernizing our basing arrangements with traditional allies in Northeast Asia — and our commitment on this is rock solid — while enhancing our presence in Southeast Asia and into the Indian Ocean. For example, the United States will be deploying littoral combat ships to Singapore, and we are examining other ways to increase opportunities for our two militaries to train and operate together. And the United States and Australia agreed this year to explore a greater American military presence in Australia to enhance opportunities for more joint training and exercises. We are also looking at how we can increase our operational access in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean region and deepen our contacts with allies and partners.

How we translate the growing connection between the Indian and Pacific oceans into an operational concept is a question that we need to answer if we are to adapt to new challenges in the region. Against this backdrop, a more broadly distributed military presence across the region will provide vital advantages. The United States will be better positioned to support humanitarian missions; equally important, working with more allies and partners will provide a more robust bulwark against threats or efforts to undermine regional peace and stability.

But even more than our military might or the size of our economy, our most potent asset as a nation is the power of our values — in particular, our steadfast support for democracy and human rights. This speaks to our deepest national character and is at the heart of our foreign policy, including our strategic turn to the Asia-Pacific region.

As we deepen our engagement with partners with whom we disagree on these issues, we will continue to urge them to embrace reforms that would improve governance, protect human rights, and advance political freedoms. We have made it clear, for example, to Vietnam that our ambition to develop a strategic partnership requires that it take steps to further protect human rights and advance political freedoms. Or consider Burma, where we are determined to seek accountability for human rights violations. We are closely following developments in Nay Pyi Taw and the increasing interactions between Aung San Suu Kyi and the government leadership. We have underscored to the government that it must release political prisoners, advance political freedoms and human rights, and break from the policies of the past. As for North Korea, the regime in Pyongyang has shown persistent disregard for the rights of its people, and we continue to speak out forcefully against the threats it poses to the region and beyond.

We cannot and do not aspire to impose our system on other countries, but we do believe that certain values are universal — that people in every nation in the world, including in Asia, cherish them — and that they are intrinsic to stable, peaceful, and prosperous countries. Ultimately, it is up to the people of Asia to pursue their own rights and aspirations, just as we have seen people do all over the world.

IN THE LAST decade, our foreign policy has transitioned from dealing with the post-Cold War peace dividend to demanding commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan. As those wars wind down, we will need to accelerate efforts to pivot to new global realities.

We know that these new realities require us to innovate, to compete, and to lead in new ways. Rather than pull back from the world, we need to press forward and renew our leadership. In a time of scarce resources, there’s no question that we need to invest them wisely where they will yield the biggest returns, which is why the Asia-Pacific represents such a real 21st-century opportunity for us.

Other regions remain vitally important, of course. Europe, home to most of our traditional allies, is still a partner of first resort, working alongside the United States on nearly every urgent global challenge, and we are investing in updating the structures of our alliance. The people of the Middle East and North Africa are charting a new path that is already having profound global consequences, and the United States is committed to active and sustained partnerships as the region transforms. Africa holds enormous untapped potential for economic and political development in the years ahead. And our neighbors in the Western Hemisphere are not just our biggest export partners; they are also playing a growing role in global political and economic affairs. Each of these regions demands American engagement and leadership.

And we are prepared to lead. Now, I’m well aware that there are those who question our staying power around the world. We’ve heard this talk before. At the end of the Vietnam War, there was a thriving industry of global commentators promoting the idea that America was in retreat, and it is a theme that repeats itself every few decades. But whenever the United States has experienced setbacks, we’ve overcome them through reinvention and innovation. Our capacity to come back stronger is unmatched in modern history. It flows from our model of free democracy and free enterprise, a model that remains the most powerful source of prosperity and progress known to humankind. I hear everywhere I go that the world still looks to the United States for leadership. Our military is by far the strongest, and our economy is by far the largest in the world. Our workers are the most productive. Our universities are renowned the world over. So there should be no doubt that America has the capacity to secure and sustain our global leadership in this century as we did in the last.

As we move forward to set the stage for engagement in the Asia-Pacific over the next 60 years, we are mindful of the bipartisan legacy that has shaped our engagement for the past 60. And we are focused on the steps we have to take at home — increasing our savings, reforming our financial systems, relying less on borrowing, overcoming partisan division — to secure and sustain our leadership abroad.

This kind of pivot is not easy, but we have paved the way for it over the past two-and-a-half years, and we are committed to seeing it through as among the most important diplomatic efforts of our time.

Hillary Clinton is U.S. secretary of state.

'아시아 회귀 (Pivot to Asia) 정책'

TPP (Trans - Pacific Partnership)

환태평양 경제 동반자 협정

Time to Get Tough

Donald J. Trump

"오바마는 세계무대에 중국을 정당한 국가로 등장시켰다.

그러나 그 대가로 받아 낸 것이 무엇인가?"

George P. Shultz (1920~)

제60대 美 국무장관

"틀렸소. 그곳은 당신들의 나라들이 아니요.

당신들은 미국을 대표하고 있는 것이요"

"트럼프 정부는 레드라인이라는 단어를 언급하는데

신중한 필요가 있습니다.

빈 협박은 결국 아군을 파괴할 겁니다.

레드라인을 언급한 이상,

우리는 적을 쏴 죽일 준비가 되어 있어야 하죠."

George P. Shultz (1920~)

제60대 美 국무장관

❝

I'm going to bring

the jobs back

from China.

❞

"The Globalist gutted the American Working Class

and created a Middle Cass in Asia"

"세계화주의자들은

미국은 노동계층을 파탄내고,

아시아이 중산층을 창조했다"

Stephen Kevin Bannon (1953~)

前 백악관 고문

US News and World Report

Trump가 추천한 책 10권

2016. 6. 1

The Art of War - Sun Tzu

손자병법

The Prince - Machiavelli

군주론

The Power of Positive Thinking - Norman Vincent Peale

적극적 사고방식

Ideas abd opinions - Albert Einstein

Essays, lectures and orations - Ralph Waldo Emerson

The Party - Richard McGregor

On China - Henry Kissinger

Mao : The Unknown Story - Jung Chang, Jon Halliday

Tide Players - Tide Players_Jianying Zha

One Billion Customers - James McGregor

National Trade Council

국가 무역 위원회

Peter Navarro (1949~)

The Coming China Wars (2006)

Death by China (2011)

Crouching Tiger (2015)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QExQUEnOxQM

'이춘근의 국제정치' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 32회 트럼프의 협상방식 (0) | 2021.11.19 |

|---|---|

| 31회 공산주의자들의 협상방식 (0) | 2021.11.17 |

| 29회 인물탐구, Mike Pence 美 부통령 (0) | 2021.11.14 |

| 28회 미국의 대북한 대화조건 (0) | 2021.11.10 |

| 27회 Rod from God (Kinetic Weapon) (0) | 2021.11.08 |